An Interview with Mike Johnson

It’s hard to find musical heroes as an adult. Sure, there are great albums being published all the time, some of them even by fresh faces. Yet, it has been a long while since anything has impacted me in the same way that King Crimson, Yes, Rush, Miles Davis or John Coltrane did when I was between fifteen and twenty years of age. The band Thinking Plague is an exception, as I only discovered it in 2017 when they published their latest album Hoping Against Hope. From the first few measures, something in the band’s music spoke to me directly, and the band soon rose to that special category of favorites, inhabited by the heroes of my youth. The music is not based on riffs, nor is it driven by the individualist expression of instrumentalists or vocalists, but rather by the pen of its composer; the music is complex but such complexity serves a musical purpose unlike is the case in so much of progressive rock and metal.

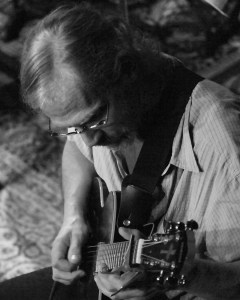

I soon discovered that the contemporary Thinking Plague serves the muse of Denver-based guitarist/composer Mike Johnson. The band performs Mike’s music, arrangements and lyrics. Something in Johnson’s musical persona started to fascinate me. The economic realities of contemporary music business should work against the creation of such music, in particular in the US which lacks many of the tax-financed institutions supporting the work of European non-mainstream artists. Who was this Mike Johnson, and how had he managed to produce seven Thinking Plague albums, many of which can easily be called works of art?

My questions were answered in early November 2018 when I got a chance to chat with Mike Johnson for two hours. I reached him at his home, a log cabin style house 7,300 feet of elevation in the mountains outside Denver, Colorado. Sporting a ponytail of silvery hair, Mike strikes me as two decades younger than his true age. We immediately launch into the interview; I get the impression of a sharp, inquisitive mind. Mike appears as keen to discuss his own music as well as the music of concert music composers or favorite bands. During the interview, I find myself building an image of a socially conscious musician who has made a career of challenging himself.

The rock-musicians of Thinking Plague skillfully and proficiently play a profound and complex form of contemporary concert music. Their musical expression can be viewed as a continuation of the work of groups such as Henry Cow, rock musicians who seriously explored the implications of modernism in concert music. Thinking Plague, though, appears to have crossed the boundary of rock music in to unknown territory. “I know what you mean, but I’m always telling people that we are actually a rock band – at least if you consider the instrumentation. And I do hope our music ‘rocks’, assuming you get to know it well enough”, Mike exclaims.

“I do hope our music ‘rocks’, assuming you get to know it well enough!”

Unsentimental nostalgia

The music of Thinking Plague strikes me as characteristically modern and European, without a markedly American sound. This does not seem to surprise Mike. ”I have listened to numerous European composers. Shostakovich, Britten, early Stravinsky. I do listen to a lot of European concert music. Come to think of it, you can hear the influence of [modern Finnish composer] Einojuhani Rautavaara’s Angel of Light symphony in the floating chords, 2:30 minutes and again at 6:20 into the title piece of Hoping Against Hope.”

I see some of Mike’s comfortable and spacious living room as a background for the video call, and the space strikes me as being in contrast with the more ascetic soundscape of his music. The living room almost makes me feel nostalgic. I can also clearly place the living room in the US. How does Mike feel about the US and the American dream? “Actually, I’m pretty anti-patriotic. I view myself as a world citizen, and I detest nationalism, except in a few cases where the identity and culture of nation in question was almost extirpated by imperialism or colonialism. A favorite example is Ireland. Also, Catalonia… I guess I should say that I’m glad of their focus on, and appreciation of, their own cultures and nationhood, versus “nationalism,” which implies a kind of aggressiveness and assumed superiority”, Mike elaborates.

Both of us enjoy the music of [US composer] William Schuman, for instance, but where I hear the sound of the “great prairies”, Mike hears cultural influences ranging from jazz to traditions of folk music. “I do experience nostalgia, in particular when I listen to some music”, Mike explains. “For instance, I heard Aaron Copland’s Billy the Kid when I was just three years old, and it left a lasting impression. When I hear it today, it transports me back. I don’t feel ‘warm and fuzzy’ when I feel nostalgic, however. When I think of ’nostalgia’ in music, it’s a sense of things gone by, or lost; maybe some happy memory but overlaid with a feeling of sadness or regret. Bitter-sweet. It’s often very abstract – not fixed to a specific time or place. I was kind of referring to this feeling in the lyrics of “Hoping Against Hope”, the title track of the new albom: ‘Visions of times unseen….memories of dear places…we’ve never known…’”

”Thinking Plague”, the name of the band, refers to suffering as a result from not being able to stop thinking about the state of the world. Hoping Against Hope refers to mounting despair as the contemporary world experiences more and more difficult challenges. Mike thinks back on his childhood in the 50’s and 60’s: “Those were in many senses more hopeful times. The biggest fear was nuclear conflict with the Soviet Union. But that was a simpler problem than climate change, for instance. I remember seeing Nikita Khrushchev’s visit to the US; him looking like a small, funny farmer, beating his shoe on a lectern as he lectured the Americans!”, Mike recalls, “it was as if the whole good guy/bad guy dynamic with the Soviet Union lost its foundation. When I reached teenage in 1965, Vietnam began to dominate the news, and to threaten peoples’ comfortable, sheltered American lives. Yet those fears pale in comparison to what we are facing today. What we are left with is ‘Hoping Against Hope.’”

A human voice, surrounded by complex music

This is in many ways a good description of what I hear in the sound of Hoping Against Hope: a beautiful lament, performed by the hopeless. Demanding, modern harmonies are expressed through sublimely beautiful arrangements in a manner which reminds me of the works of Alban Berg and Arnold Schönberg. Yet, Mike insists that he wants the music to be able to reach and communicate to audiences: “I never use the 12 tone method. So, I don’t want people to deal with total atonality when they attempt to “penetrate” Thinking Plague’s music. That’s why I usually refer to those 20th century masters who employed ‘extended tonality’, such as bi- or polytonality. I believe I really got my first and most important understanding and love of ‘more-than-tonal’ harmony from Shostakovich. Then there’s William Schuman, whose progress from sophisticated tonality to extremely extended tonality can be traced through his symphonies… Prokofiev in some of his pieces, Britten, Bernstein. Aaron Copland composed “serious music” such as his Short Symphony (No. 2) as well as ‘accessible’ music, but with much integrity and quality (Billy the Kid, The Red Pony, and so on).”

The contrast between the innocence of Thinking Plague vocalist Elaine Di Falco’s voice and the tonally complex and polyrhythmic instrumentation is another way of making complex musical ideas accessible. Mike Johnson tells me that Di Falco’s natural range is contralto, but as the composer of Thinking Plague, he wants to write to her higher register. “The human voice has a special role in our music. Its role is to provide a counterweight to the more austere instrumental score.”

“Because of the level of concentration that the vocal part requires from the singer, you will find none of the ‘posing’ that’s so common to rock singers. That said, Elaine, is the first and only Thinking Plague singer who can and actually does emote, and looks ‘cool’ on stage sometimes”, Mike laughs.

Di Falco has contributed vocals to other ambitious bands such as the experimental pop group Caveman Shoe Store and the prog rock group Combat Astronomy. The Italian group Yugen provides a particularly interesting perspective to Mike’s approach to writing for Di Falco. Mike, Elaine and a number of other musicians play on Yugen’s album Iridule, and Elaine sings in her natural lower register. Johnson reports an admiration to the musicality of Francisco Zago of Yugen, noting that he is also “a really smart guy.”

Elaine Di Falco sings in the contralto range on Yugen’s album Iridule

From musical fusion into musical modernism

The history of Thinking Plague starts in 1982 when Mike Johnson founded the group with his partner, multi-instrumentalist Bob Drake. The group’s first two albums: A Thinking Plague and Moonsongs were re-issued by Cuneiform on one CD in 2000, under the title Early Plague Years. The albums were originally very limited vinyl pressings that have been out of print since the 80s.

These, and the next two albums: In This Life, In Extremis, represent a stylistic union between Johnson’s modernist ambitions and the influences brought by co-founder Bob Drake. “When we were first starting Bob’s big influences were prog rock groups such as Yes, Henry Cow, and Art Bears, but he was also then playing in some new wave bands, which probably influenced him. He had also had an interest in what we call ‘hillbilly’ and old Cajun music with fiddle.”

Mike tells me that in the band’s early days, Drake and he “had an ethic we called ‘hi-lo fi’ that referred to our love of trying to make very hi-fi recordings using cheap equipment, bad spaces, and so on: what people often refer to as ‘DIY.’ But we hadn’t heard that term yet. It was something that, of course, we had little choice about, but the 80s, with the ‘independent record label’ phenomenon, were a time when experimentation with recording sound, instrumentation, styles and everything else was more appreciated, even expected. “

Indeed, a comparison between In This Life and Hoping Against Hope demonstrates an interesting arc from the energetic musical fusion of the group’s early days towards a mature, deliberate and modernist compositional language. In This Life was the band’s breakthrough, and in a sense it is their most fashionable album. Vocalist Susanne Lewis contributed to songwriting, and her influence brought a touch of New Wave into the mix. I can even detect a hint of early Talking Heads in there. The album also has a significant world music influence, ranging from the Balkanese-sounding opener “Lycanthrope” to the gamelan-sound of “Organism II.” “That was the result of having drummer Mark Fuller involved. He owned and knew how to play tabla as well as bamboo marimba and other Indonesian percussion”, Mike tells me.

Balkanese-sounding song “Lycanthrope” opens the album In This Life

You can listen to the entire album at https://cuneiformrecords.bandcamp.com/album/in-this-life.

Johnson tells me that In This Life remains Thinking Plague’s best-selling album. He acknowledges the contribution of publisher Chris Cutler, former drummer for the band Henry Cow in promoting the album. “Chris made the album available world-wide through his network of distribution and direct mail order catalogue, Recommended Records.”

Mike perceives some of the material In Extremis (1998), which follows In This Life as “the next step of my development as a composer. The album also included some older material that had been recorded by the 1990 incarnation of the band – Dave Kerman on drums, Bob Drake on bass, Shane Hotel on keys, Mark Harris on reeds, but no more Susanne Lewis, who had left for New York City to pursue her more punk/underground kind of music. Bob Drake did a great job in mixing the diverse material together into something which made sense”, Johnson explains.

“Behold the Man”, the austere second track on In Extremis contains some wild guitar work by Mike Johnson.

You can listen to the entire album at https://cuneiformrecords.bandcamp.com/album/in-extremis

The tune ”This Weird Wind” from In Extremis has an interesting Yes-influence. Mike tells me that the influence was not pre-planned. “It was never intended as an homage to Yes. I got together to work on the song which I had written previously with Bob, Dave and Sanjay Kumar (5UUs, U-Totem) for a week in LA in 1991. We started recording it right after that. Apparently Bob and Dave were thinking it might be something for a new band. But that never happened, and I didn’t want the song to be ‘orphaned’ forever, so I included it. To me it was as much Thinking Plague as anything else, but with a different keyboardist. The only thing about it that I thought was maybe kind of ‘Yessy’ was the finger-picked acoustic part. Otherwise, I was just letting my inner ‘progger’ write the song. But Bob’s vocal part, mainly because of his range and timbre, I think, added a lot of ‘Yessiness’. It just kind of happened. We were old 70s Yes fans.” Mike tells me that in retrospect, ”This Weird Wind” could be perceived as an exploration of where Yes would have ended up, had they traveled the road which they started on the album Relayer.

Madness, served in two ways

Mike Johnson feels that A History Of Madness (2003), the album that followed In Extremis, was stylistically more coherent than its predecessor. “There is at least a double entendre in the album’s title. Bob Drake was at that time living in the south of France in an area that was the arena for the so-called Albigensian crusade in the 14th century”, Johnson explains. The target of the crusade was an offshoot sect of Manichaeism, a religion related to Christianity, the growing influence of which pleased neither the king of France or the Pope. The crusades resulted in yet another “cleansing” of the Christian faith by the sword, and the seizing of the Cathar lands and wealth as spoils; “the true motivation for many of the so-called crusaders”, Mike adds. The results were so encouraging that the Pope founded a new institution called the “Inquisition”, initially to eradicate the remaining pockets of Catharism in Languedoc and Midi-Pyrenees regions.

”I wrote the musical motifs for the album while staying at Bob Drake’s place during the 5UUs European tour in the year 1995. I continued working on the music at home in Denver between about 1998 and 2002. I read into history and cultural anthropology and spent a fair amount of thinking about the role of hero worship in the history of mankind”, Mike elaborates. ”The double entendre of A History of Madness stems from the fact that during my reflections of such dark moments in history, I was personally suffering from depression. In this sense, the album is a story of not only the history of madness in mankind, but also a story of my own ‘clinical history’”, Mike enlightens me. ”For instance, the song ’Blown Apart’ is clearly about mental health, while ‘Consolamentum’ directly refers to an incident during the end of the crusade, the siege of Monsegur. Consolamentum was a Cathar ceremony for one to become a “parfait’ or perfect Cathar.”

A History of Madness is structured in an interesting manner. Between longer pieces, the album features a series of four short pastiches called ’Marching as to War’, performed by up to eight pianos. Johnson feels that ”because of the way it is structured, the album gives the impression of being a concept album. I did, however, want to leave open the interpretation of this concept.” In passing, Mike mentions that he would like to remix the album at some point in the future.

The sinister “Gúdamy Le Máyagot (An Phocainn Theard Deig)” from the album A History of Madness.

You can listen to the entire album at: https://cuneiformrecords.bandcamp.com/album/a-history-of-madness

Free from the ground, free from the guitar, free from improvisation

There does not appear to be a lot of room for improvisation in the music of Thinking Plague, which Mike Johnson readily admits. ”As a guitar player, I like improvising, of course. As a listener, however, I have little patience for it. The whole head-solos-head structure in jazz music seems pretty boring to me. That is, I have little patience for noodling in my own music or the music that I listen to.”

I ask Mike to elaborate on his relationship with the guitar. Concert music composers were almost without exception virtuosi of their instruments. Bach was a renowned organist, Mozart and Beethoven built their reputation as pianists before becoming known as composers. Vivaldi was a master of the violin. Johnson is skilled guitar player. There is a lot of innovative guitar work in the arrangements of Thinking Plague albums. “This band was not created as a platform for my playing”, Mike tells me, but continues, “that said, I did want to showcase written parts for guitar, my techniques and my harmonies and rhythms – with the occasional guitar ‘solo’. For example the guitar solo, at 8:43 minutes in ‘Dirge for the Unwitting’ (from Hoping Without Hope) is pre-composed, as is the one in ‘Climbing the Mountain’ (from the album Decline and Fall) at 6:12 minutes. I’m generally not quite smart or skilled enough to ’whip out’ something like these off the top off my head!”

Improvisation tends to service textural rather than melodic purposes in Thinking Plague’s music, and solos with heavier melodic content tend to be composed. “Earlier in the song ‘Climbing the Mountain’, at 1:07, there is an improvised guitar solo…but it’s completely unorthodox, just me making havoc with Digitech Whammy pedal. I don’t think much of it, but it serves its purpose. On A History of Madness in the song ‘Consolamentum’ at 3:22, there is another fully improvised solo, not mixed very prominently, that I literally did off the top of my head, while sitting in front of my computer. Again, very unorthodox. Also we sent some of the signal into a synth effect that was unable to track the guitar accurately. We thought it was funny and bizarre, so we mixed enough of that in to make you go: ‘What the hell’s that?’ Later on the album A History of Madness, in ‘Lux Lucet’ there’s another precisely composed solo section for the guitar at 2:11. I’m proud of it, as a guitar figure, but it’s nothing special technique-wise compared to today’s shredders”, Mike reflects.

When I tell Mike that I am also a guitar player, he tells me that Yes maestro Steve Howe is a significant early influence and asks me if I can hear Howe’s influence in his playing. I tell him that I only hear Howe in the song “This Weird Wind”. What I hear instead in the guitar arrangements is quite a bit of Robert Fripp and King Crimson. “OK, that’s fair. In a way I was raised on Robert Fripp: that wonderful fuzz-sound that Fred Frith also had”, Johnson responds excitedly. He picks up an electric guitar and starts playing passages from Thinking Plague songs. As I listen, my fingers silently travel those roads that they used to travel while I was learning to play King Crimson songs. “In retrospect, Gentle Giant was clearly the best prog rock group of them all”, Mike reflects, “and Henry Cow was the most sophisticated. Then again, I have learnt all the fundamental ‘guitar’ stuff”, Mike notes and plays a couple of blues licks. “I have also co-organized a Beatles tribute-project which gives me a little extra income and some extra fun!”

Mike Johnson co-organized a Beatles tribute band. He writes their orchestral arrangements.

Thematic development instead of cut and paste

Johnson appears pleased when I tell him that the two latest Thinking Plague albums Hoping Against Hope (2017) and Decline and Fall (2012) sound like a stylistically continuous pair, resulting from a long process of musical maturation. “With these two albums, I feel that I have come closer than ever to realizing my compositional goals.” He tells me he is happy for having ”finally found a way of working where I am not at the mercy of inspiration. While inspiration does happen, I no more have to have a perfect complete idea come to me.”

Mike has a very well-elaborated view of his compositional process: “The seeds of my compositions are often in rhythmic ideas; in this sense I am a rocker at heart. I hear constant music in my head. I start working these seeds on the computer, using the program Finale. I am not a planner in how I work, because I do experiment quite a bit. The little motifs, grooves and stuff that come into my head have to be fleshed-out, developed. My brain has adjusted to being capable of filtering whatever musical material that comes to me. I no longer need a mind-blowing riff to get going, but rather work on developing and expanding musical themes. When I get an idea, I scribble it down in a notebook. And sooner or later I may transfer it into Finale, where I begin developing and expanding it until I am completely happy with the outcome. I am relentless in not wanting to publish anything that I am not completely satisfied with.”

”My brain has adjusted to being capable of filtering whatever musical material that comes to me.”

Something in Johnson’s story reminds me of philosopher Decartes’ pursuit to accomplish control of the spirit by overcoming the limitations of the flesh. A guitar player seeks to rise above his instrument, to use his brain in the compositional process rather than relying on his fingers or his gut. How fast is his process of composing; say ”Malthusian Dances”, the opening track of Decline and Fall, whose the devilishly complicated 19/16 riff took me an hour to figure out? Was it as complex to compose as it was for me to disentangle as a listener? Mike tells me that the rhythmic idea itself only took him a couple of minutes to put together, but the process of developing themes takes much more time. “I often begin with a rhythmic idea like that, and continue by figuring out a bass-line. Then I start on harmony and thematic development. I had a stage in my career as a composer when I liked to show off with complex rhythms and stuff. Later in life, I have wanted to approach rhythm and the whole composition in a manner similar to concert music composers. From this standpoint, djent music and all this math metal that you hear a lot these days, sounds hollow; empty posing in a garage, devoid of musical substance”, Johnson exclaims.

Fans had to wait for Decline and Fall (2012) for almost ten years following the release of A History of Madness. The fans’ patience was rewarded, however, as the album is a masterpiece and in my view clearly outshines everything that came before.

The introduction of Elaine Di Falco’s voice is like the cherry on top of a cake. As a composer, Mike Johnson seems to have taken a decisive step forward, as he writes music that is simultaneously incredibly advanced and complex, yet it breathes to a natural rhythm. The music is simultaneously demanding and approachable. ”The pulsating rhythm of Rock-music is like a ground I stand on. Yet, I want to take flight, to free myself of the earth by letting my brain process new possibilities in the musical themes that I hear”, Mike Johnson reflects on his compositional practice.

“The pulsating rhythm of Rock-music is like a ground I stand on. Yet, I want to take flight, to free myself of the earth by letting my brain process new possibilities in the musical themes that I hear.”

”While I was writing Decline and Fall, I finally felt I was free of the guitar. Before this, my process of composing was controlled more by my fingers: for instance the song ’A Rapture of the Deep’ on A History of Madness sounds to me like something written by a guitar player. In writing Decline, I did not have to spend as much time with a guitar in my hand, waiting for inspiration.

I had reached a level in my work process, where I could process material primarily on the computer. I try out all sorts of things, combine themes and develop them further by injecting all sorts of ideas. I particularly like the notion of a theme returning; you hear this in a lot of concert music, you know, when previous themes are re-introduced in the context of what has happened in between”, Johnson explains.

An excerpt of the politically charged ”Sleeper Cell Anthem” from Decline and Fall.

You can hear the entire album at: https://cuneiformrecords.bandcamp.com/album/decline-and-fall-2

Thinking Plague’s latest album, Hoping Against Hope (2017) was published six years after its predecessor, which is fast relative to the previous albums. The thematic approach to composition that Mike Johnson had been working so hard to master reaches its zenith on the album. I ask Mike to explain how he manages to create such intricate polyphonic patterns, and how he manages to orchestrate them in ways that make the instrument resonate so beautifully with each other. “On the new album, I approached orchestration in the following way. I often started with a bass line and continued by developing a melody to accompany it. I then thought about harmonic development, and implemented chords into counterpoint, that is, individual voices played on different instruments”, Mike explains, “I use my inner ear, my aural imagination. When I get an idea, motif, guitar thing, and so on, I start to hear things that go with it.”

Johnson departure’s from the practices of writing rock music is most evident in his focus on developing themes. “I want all the musical pieces to fit together. First and foremost, I want to avoid any kind of ‘cut and paste’ where riffs or melodies are glued together, which is often the practice in writing rock music. On the latest album, I approached the trio of two guitars and soprano saxophone as a harmonic core, and the individual voices of this trio as producers of harmonic movement. This idea is clearest on the songs ‘Hoping Against Hope’ and ’A Dirge for the Unwitting.’”

“Echoes of Their Cries”, opening track of Hoping Against Hope.

You can listen to the entire album at https://cuneiformrecords.bandcamp.com/album/hoping-against-hope

The future of Thinking Plague

Mike Johnson’s life appears to be filled to the rim with music. He is writing new material for Thinking Plague and plays in, and arranges for, The Rubber Souls, a Beatles-tribute band. He also performs in the avant-folk group Hamster Theatre, as well as a band called Revelator, which targets a more commercial audience. Mike also mentions in passing of just having finished a strings and horns infused instrumental arrangement of ”Dead Silence”, the opening track In Extremis to be published as a printed score by an Italian publisher.

Mike Johnson’s lighter side can be heard in the recordings of Hamster Theatre.

Despite all this energy and enthusiasm, Johnson has balanced his entire musical with a demanding day job. He tells me he worked in social work and educational projects aimed at increasing “education levels and employment opportunities for economically disadvantaged populations – the poor, minorities, the homeless, mentally ill, ex-offenders (felons), and so on.”

I also get the impression that each new Thinking Plague album is a Herculean effort, both in terms of the money and organizational effort required. ”I am a perfectionist, both when it comes to recording or live performance. I work with skilled musicians, but they too have several priorities in their lives”, Johnson tells me. Vocalist Elaine Di Falco has just finished a second master’s in music. Sax player Mark Harris is a professor of his instrument with all the responsibilities that come with the role. Drummer Robin Chestnut has a PhD in mathematics (this, quite frankly, should not surprise anyone!) ”Recording is always a challenge to organize, even though we record each instrument individually. As a perfectionist, I have had to train myself to edit recordings”, Mike tells me.

Sympathy with Zappa

In 2004, the organizers of the festival NEARFest published Upon Both Your Houses, a Thinking Plague live album, recorded in 2000. While skeptical, Mike Johnson does not rule out the possibility of publishing more live albums. ”There are many opportunities for recording concerts. For me, making a live album requires a band that has rehearsed and performed quite a bit, however. Performing our music live requires a ’tight sphincter’, because there are so many mines that you can step on at any time”, Mike jokes.

Mike Johnson told me that while he is rarely content with recorded live performances of Thinking Plague, this performance of ”Sleeper Cell Anthem”, recorded in Austin, is an exception.

Organizing performing group appears to have been an enduring challenge throughout most of Thinking Plague’s history. “Before recording In This Life, Bob Drake and I had tried to form a live band. We played several local concerts, for which we initially rehearsed in an old warehouse space (an old yogurt factory) for a period of two sweltering weeks in mid-summer. These were the first live performances of TP music since 1983, when we gave up trying to have a live band. The next brief flurry of concerts was not until June and January of 1990. But it was after the concerts in 1987 that our main keys player and drummer left, that I started working in earnest on music for In This Life – incorporating a clarinet for the first time, because the ’other’ keys player was also a clarinetist. Then he too left, and we drafted Mark Harris to play reeds.”

Live recordings from the live band that preceded In This Life: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLftB2gYwhiFHuVsXMaEBqNfgypkwE2QlR

Johnson tells me that ”if I had the funds, I might just commission tracks from LA session musicians who will play anything they read.” He has also entertained the idea of becoming a MIDI-composer. I tell him that I see similarities with his artistic profile and that of Frank Zappa, because he too was in a sense a rock musician who worked hard to establish himself as a composer of concert music. “I must have seen Zappa’s band live seven times, and I liked him best in that context. He had access to the very best talent available and the resources to pay them for grueling all day rehearsals for months, so I’ve read”, Mike responds.

We concur that his Synclavier albums don’t represent the best of Zappa’s published output, and Mike has managed to resist the urge to publish music performed by computers. ”I have to say though that the computer is a great tool for a composer. The song ’Thus We Have Made the World’, on Hoping Against Hope, is a fun example. There was an error in the Finale program, and two themes from completely different parts of the score were glued together. This sounded really fun and I started developing that idea, and ended up implementing it on the finished song in those accordion chords in the last section.”

Mike Johnson appears to be filled with musical passion and ambition. Despite the numerous difficulties involved, I bet my lunch money that Hoping Against Hope will not be the last word from Thinking Plague. In any case, the band’s published output, spanning three decades, is a treasure trove for the bold listener. This band is the best kept secret in the music business.

Text: SAKU MANTERE

Read also:

- An exhaustive interview with Mike Johnson https://nmbx.newmusicusa.org/mike-johnson-thinking-plague/

- A 2+ hour podcast interview with Elaine Di Falco ja Mike Johnson featuring a lot of music https://www.mixcloud.com/progrockdeepcuts/deep-cuts-148-featuring-thinking-plagues-mike-johnson-and-elaine-di-falco/?fbclid=IwAR0FhPwsKb6lVE1xDSxlQ11m4IwFtjv3TQdxxZxV6LE_Ld_nz3vsNI6MIRQ